Paffard Keatinge-Clay

Paffard Keatinge-Clay (1926-2023) was a significant architect of the 1960s and 70s whose body of work, while limited in the number of built works, left an indelible mark on the San Francisco Bay Area. With a keen eye for material and geometry, Keatinge-Clay created some of San Francisco's most remarkable Modernist buildings. Although not a household name like Frank Llyod Wright or Anshen & Allen, his influence on the next generation is demonstrable through recorded lectures and the praise of other architects.

Docomomo-US Northern California documents Keatinge-Clay's work in the region. By highlighting his achievements and shedding light on his impact, we hope to increase recognition of this inventive architect and ensure the stewardship of his significant works for the enjoyment of future generations.

We hope you enjoy this tribute to a remarkable talent whose legacy still endures. Please take a moment to explore Keatinge-Clay's work and share any feedback with us at info@docomomo-noca.org.

Paffard Keatinge-Clay (1967)

Keatinge-Clay. San Francisco Art Institute

Architect, artist and designer Paffard Keatinge-Clay was an evolutionary figure in the history of Modern Architecture having attended school at both the AA in London and the ETH in Zurich, after which he worked for Le Corbusier at his studio in Paris, and Frank Lloyd Wright in Spring Green, Wisconsin and Scottsdale, Arizona. Paffard then worked in Chicago for the office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill where he was the primary author of the Harris Bank and Trust headquarters building in the Chicago Loop. He would later move to San Francisco and work on a prototype branch bank for Great Western Savings & Loan in Los Angeles for which SOM was commissioned with Dion Neutra serving as the local architect. Paffard would subsequently start his own practice in San Francisco in 1963 where he produced a remarkable series of unapologetically modern buildings throughout the San Francisco Bay area including the addition to the San Francisco Art Institute, the San Francisco State University Student Union, his own house – the “Tamalpais Pavilion”, and an addition to the French Hospital, among many others. The audaciously Corbusian addition to the Art Institute is currently under threat of demolition in the wake of the financial collapse of the school as an institution and its location in one of San Francisco’s most desirable residential neighborhoods where land and building sites are scarce. Much of his most remarkable work was never built – competition-winning proposals in London and Glasgow, Scotland.

Paffard worked briefly in Canada before settling in an idyllically sited farmhouse in rural Spain where continued to practice as an artist, author and sculptor. He and his work were the subject of the 2006 monograph Paffard Keatinge-Clay: Modern Architect(ure)/Modern Master(s).

Paffard Keatinge-Clay died on 17 March 2023 at his farmhouse in Mijas, Spain.

(Biography Courtesy of Eric Keune, Docomomo US Board)

Biography

Selected Works

Strauss Residence

1964, Diamond Heights NeiGHBORHOOD,

San Francisco CA

Strauss Residence. Designed in 1963 and completed in 1964. Fairmount Hill, Diamond Heights, San Francisco, CA.

In San Francisco's Diamond Heights neighborhood lies a modest residence that has only recently been recognized as the work of architect Paffard Keatinge-Clay. Completed in 1964, the Strauss Residence was likely one of Keatinge-Clay's first commissions when he opened his office in San Francisco in 1963.

Unlike the architect's home in Mill Valley, the Strauss Residence lacks many of his signature design characteristics, including his signature use of concrete. Nevertheless, its status as one of only two private residences Keatinge-Clay ever built is significant. Working within a middle-class family's budget rather than the resources of a large institution or corporation presented a unique challenge for the architect. It resulted in a distinctive building within his oeuvre.

The Strauss Residence appears unremarkable from the street, but the downhill-facing elevation reveals the hallmarks of a restrained, Mies-in-wood design. Initially built for the Strauss family, the home remained their residence until 2007. Subsequent renovations were necessary to address the deteriorating deck, and interior remodels the street-facing patio enclosure, and the addition of an in-law unit resulted in the replacement of many of the original interior finishes and casework. However, the living room, with its wall-to-wall window offering stunning views of downtown San Francisco, remains a testament to Keatinge-Clay's ability to create a unique space for a young family.

The Strauss Residence is located in an area that saw significant development in the 1960s and 1970s. It features several homes designed by notable local architects. More information developments can be found on moderndiamondheights.com/maps.

Mount Tamalpais Pavilion

1965, Mount TamALPAIS

Mill Valley, CA

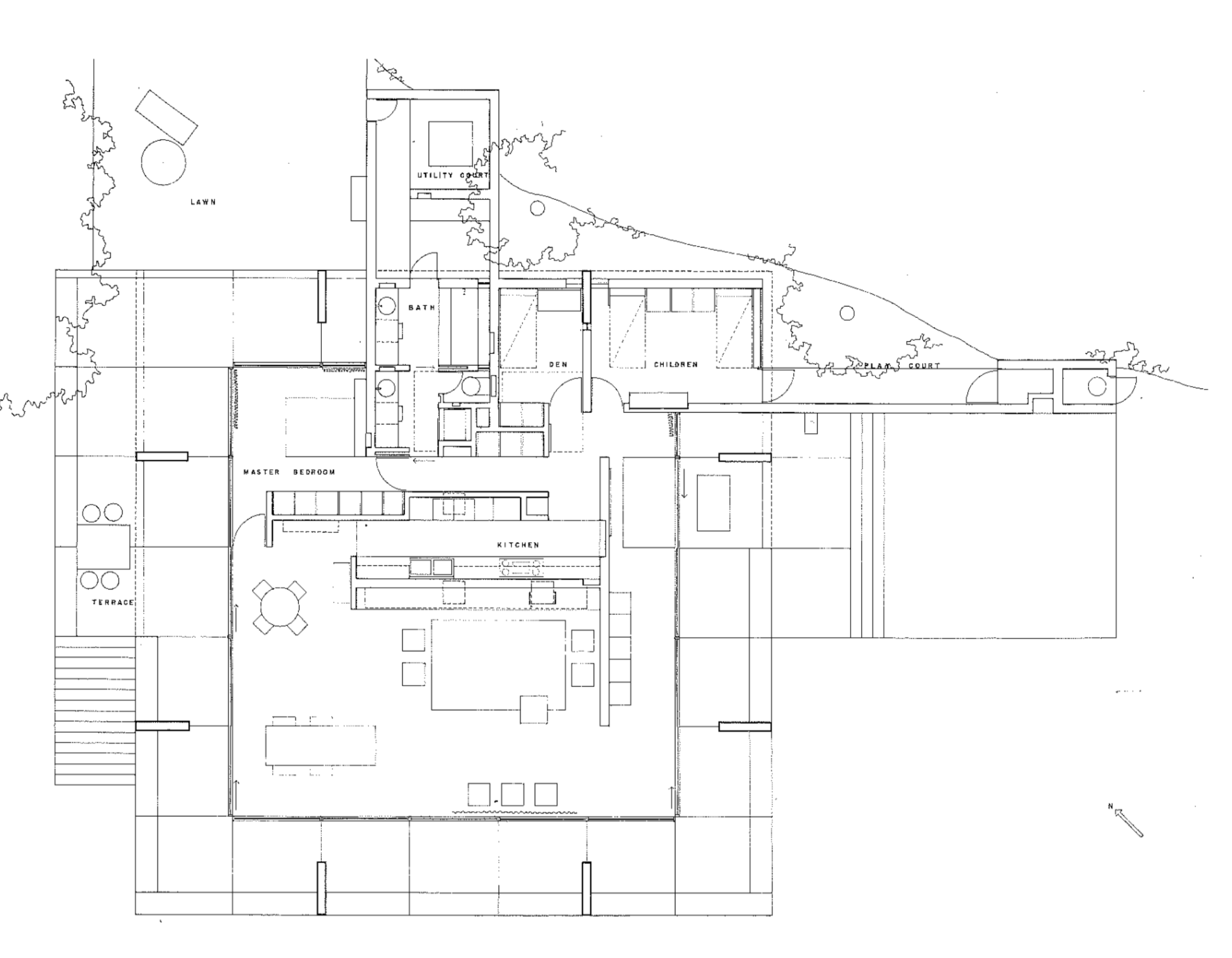

Mount Tamalpais Pavilion. Designed 1962-63 and completed 1964-65), Mill Valley, CA.

Perched on the hillside, up a steep and a remote road in Mill Valley just below the peak of Mount Tamalpais, stands an architectural marvel that is both a radical interpretation of a free plan and a tour-de-force of design and uncompromising execution. This house, the personal residence of architect Paffard Keatinge-Clay, is likely the only private residence in California to use pre-stressed concrete. Engineered with the help of French structural engineer Jacques Kourkene--collaborator on many of Keatinge-Clay’s projects--the house's eight freestanding columns define the floor plan, while glass sliders enclose the main space on all sides, offering expansive, unobstructed views of the Bay Area. The concrete building appears as an inhabitable outcropping of the hillside, fulfilling Frank Lloyd Wright’s maxim that “No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.”

The challenges of construction were significant, with all materials having to be brought up to the remote lot to accommodate the continuous concrete pour. Nevertheless, the resulting design is nothing short of monumental, with its commanding appearance over the hillside. Keatinge-Clay himself always referred to it as the "Mount Tam Pavilion."

In 1975, Keatinge-Clay sold the house to Sammy Hagar, who still owns it. Over the years, the house has undergone several additions, remodels, and landscape modifications that many consider insensitive, but a careful look reveals the original structure's enduring existence. Despite the changes, the house remains a tribute to Keatinge-Clay's visionary approach to design and construction.

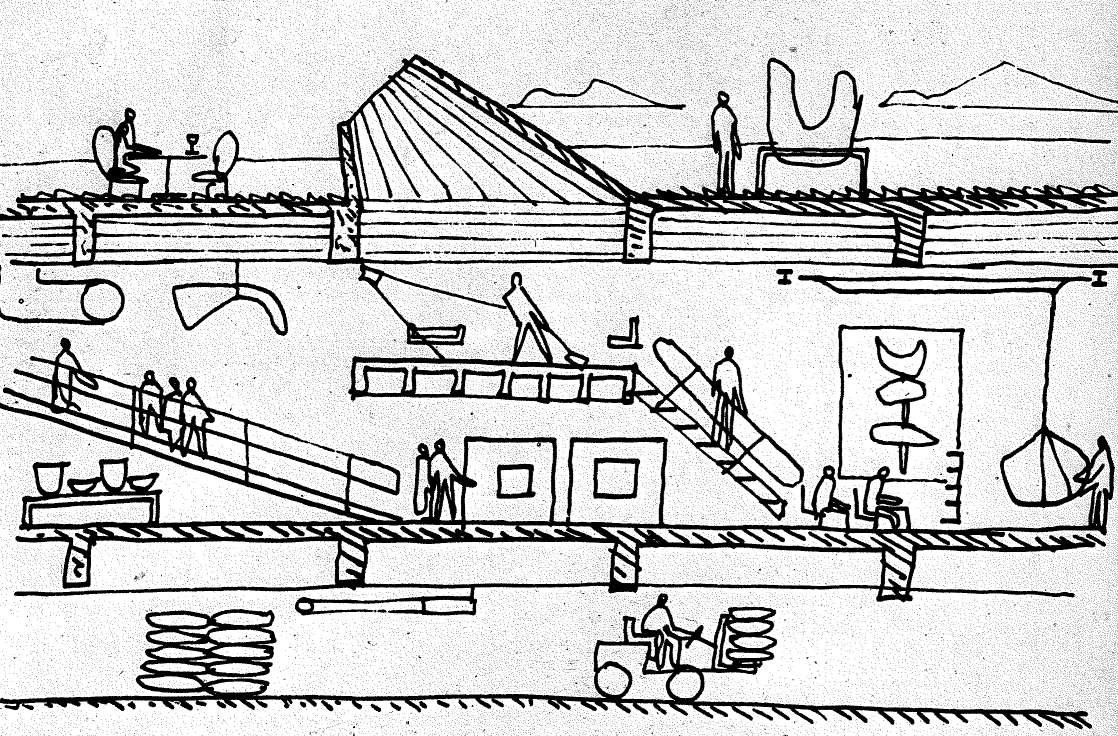

PKC explaining the structural concept and construction process.

San Francisco Art Institute Addition

1970, 800 Chestnut Street,

San Francisco, CA.

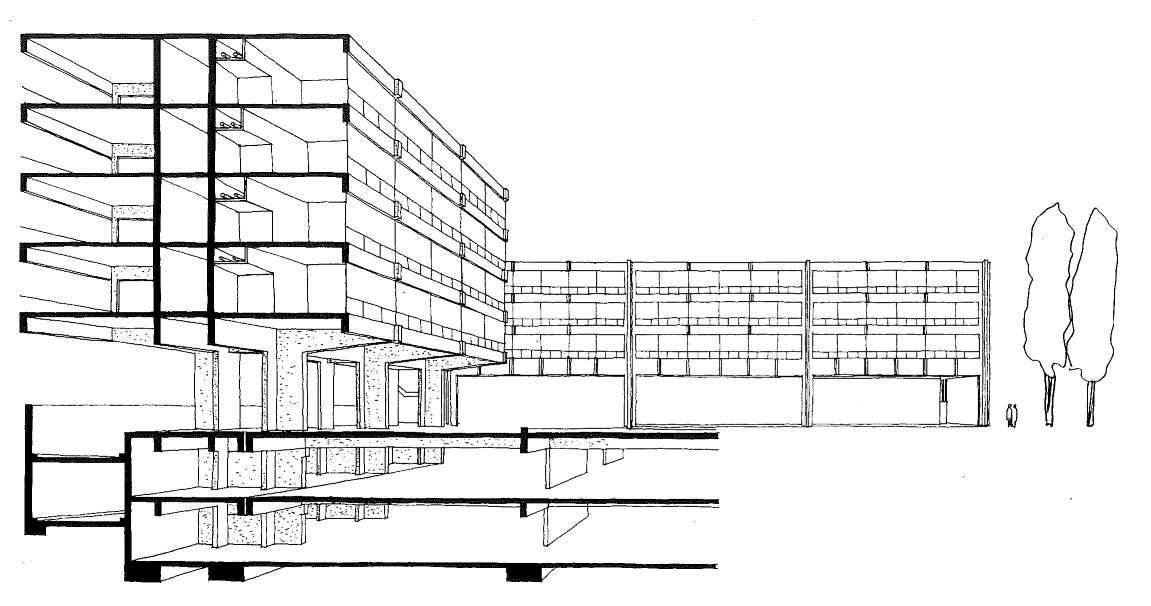

San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) Addition. Designed 1966-69 and completed in 1970. Photo by Eric Keune.

Paffard Keatinge-Clay's addition to the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) is his most significant contribution to San Francisco's architectural landscape. The exposed concrete structure was designed to house classrooms and art spaces, crowned by a rooftop terrace offering carefully framed San Francisco Bay views. Inside the square-shaped addition, a Corbusier-inspired ramp dramatically dissects some double-height spaces, adding a touch of drama to the otherwise austere structure.

Keatinge-Clay's admiration for Le Corbusier is evident in the cone-shaped skylights that sprout up through the rooftop terrace and in the downspouts and handrails, among other references. As a virtuoso of exposed concrete, he understood the impact of San Francisco's unique light on board-formed concrete, which takes on an expressive materiality and texture.

Following SFAI’s closing in 2022, the building's future remains uncertain. Nevertheless, the building's continuing impact on architecture is evident, such as in Wes Jones’s introduction to Keatinge-Clay lecture at the University of Southern California and a profile by artist Ramak Fazel (Domus December 2018).

Check out this scene from the ‘Streets of San Francisco’ (Season 5, Ep 20) - “Dead Lift”, with a cameo by an aspiring European bodybiulder.

French Hospital

1970, 4141 Geary Boulevard

San Francisco, CA

French Hospital. Designed in 1968 and completed in 1970.

4141 Geary Boulevard at 5th Avenue. San Francisco, CA. Currently, the Kaiser San Francisco French Campus.

The French Hospital buildings on bustling Geary Boulevard may not be to everyone's architectural taste, but their stark, exposed, and rational concrete facades serve as a striking visual landmark. The medical complex, designed initially as a three-winged structure with underground parking and a landscaped courtyard, occupies the entire north half of a city block. Only two wings and a below-grade structure were ultimately built, with the planned courtyard mainly serving as a parking area. Patient room wings, facing the quieter side streets, are elevated on pilotis to offer views over the surrounding two- to three-story neighborhood and exhibit clear Corbusian influences. On the other hand, the office wing along Geary Boulevard follows a Miesian concept with cross-shaped concrete columns, allowing for a column-free floor plan. Despite the original exposed concrete facades being painted now, and the constant need for changes to accommodate medical functions and advancing technology, the fact that the complex continues to be in active use is a testament to its successful response to the clients' needs.

San Francisco State University Student Union

1975, 1600 Holloway Avenue

San Francisco, cA

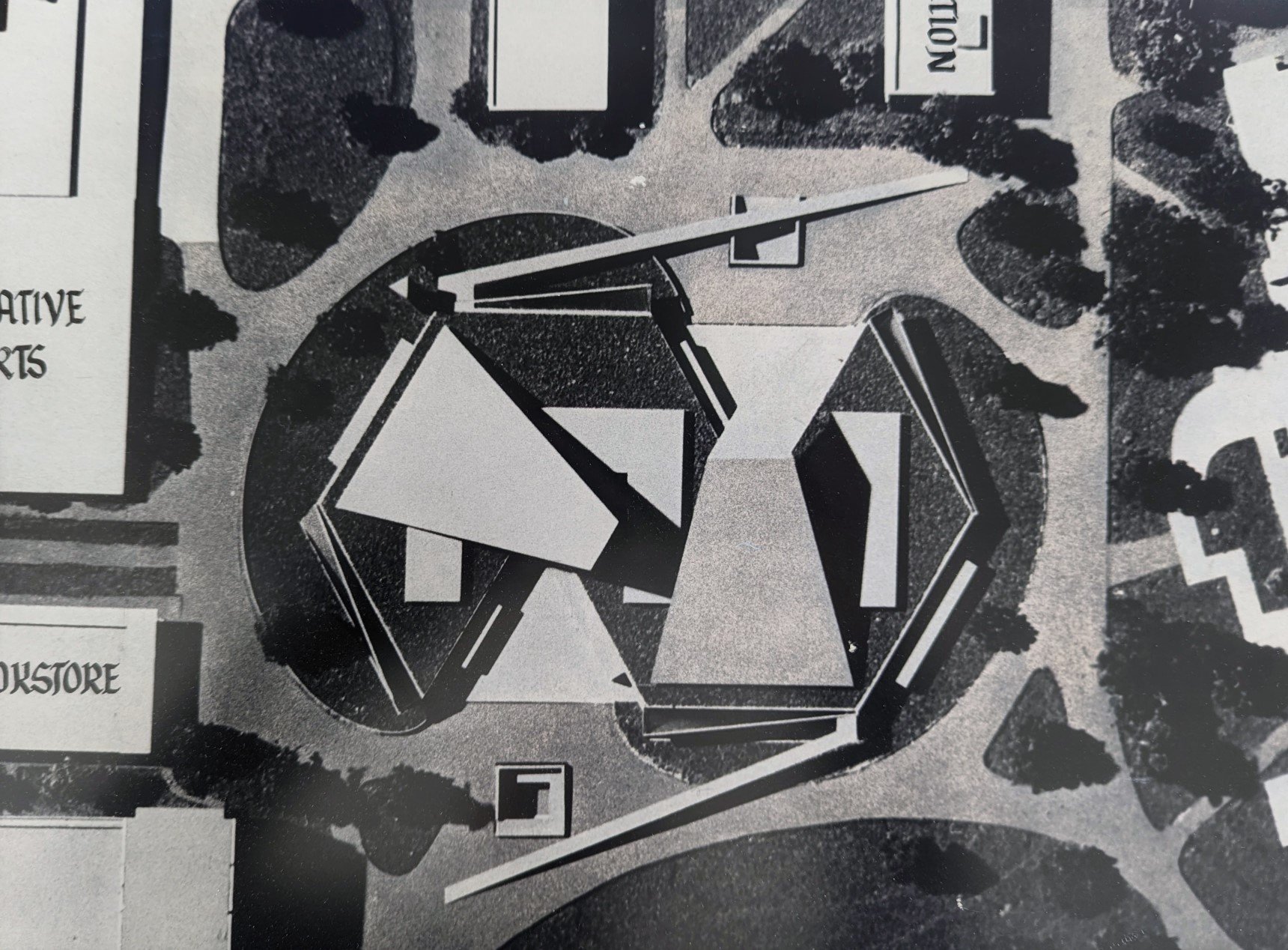

Designed between 1969 and 1973, this building directly resulted from the tumultuous student protests in 1968, in which San Francisco State University (SFSU) played a pivotal role. This is true in terms of its program and architectural expression. After SFSU’s Trustees did not approve a competition-winning Moshe Safdie design, Keatinge-Clay was awarded the project and worked with student groups on developing his new design, which was completed in 1975 after a long and complicated construction timeline.

The building represents a departure from Keatinge-Clay's earlier super-rational, cartesian designs and marks the last project he designed before leaving San Francisco. While inspired by his own earlier design for a Roosevelt memorial, the Student Union combines elements of different architectural concepts, with the structural system based on a hexagonal, Wrightian layout. In contrast, the elevation and exterior elements, like scuppers, monumental doors, carry a Corbusier-influenced idiom. The resulting building is a walkable sculpture that offers a wealth of spatial experiences.

The building's regular student union uses, such as meeting rooms, a food court, and a bookshop, are crowned by two tilted pyramidal volumes, one of which serves as a stepped outdoor performance theater. Outdoor staircases and walkways allow visitors to stroll and explore the structure from all sides, showcasing the many unique design details.

The addition of rooftop offices in the early 2000s affected the appearance. Still, the building continues to operate as envisioned initially and remains one of San Francisco's most important public buildings from the 1970s. Its architectural statement has had a lasting impact on many architects, as evidenced by Steven Holl's article in Domus from April 2023.

Open to the public on all days except Sunday during the school semester, this building is a unique space that anyone visiting San Francisco should take the time to explore. Visitors are also recommended to check out the display showcasing the building's history on the lower floor.

The building stars prominently in this “Streets of San Francisco” episode (Season 4, Ep. 19).

San Francisco State Student Union showing the massive pivot door (L) and the roof top stadium seating (R).

Ender Medical Building

1964, 141 Camino Alto,

Mill Valley, CA

Keatinge-Clay designed another medical office building during his productive late 1960s phase, this time in Mill Valley. The 2-storey building has open circulation on both levels, from where all office suites are accessed. Originally clad in redwood, the recent retrofits changed the appearance drastically. The renovation also replaced the handrails of the exterior staircase, which is still showing some of the concrete formwork that Keatinge-Clay is known for, with new different, current building code compliant handrail. On the backside, some of the original details, like window framing and cross bracing, can still be seen. (State: 2023).

Photos of the building after a 2022 renovation.

Novato Professional Building

1965, 1615 Hill Road,

Novato, CA

This square-shaped one-storey office building, mostly used by medical professionals, consists of 4 identical wings, arranged around a central courtyard from where all professional/medical offices are accessed. The building frame is actually concrete; though only expressed in the columns. Both street and courtyard sides have a very generous roof overhang, explaining the substantial depth of the roof system, that is expressed with the fascia. Originally clad in redwood, it's now covered with metal siding. The non-structural wooden brise soleils carry nice, sharp edge details; and give it a sophisticated and reserved look from the street, now unfortunately covered by tall oleander shrubs.

Lecture Recordings

SciArc 1979: Paffard Keatinge-Clay (March 12, 1979)

SciArc 2006: Paffard Keatinge-Clay The case for the individual (March 22, 2006)

USC 2016: Paffard Keatinge-Clay: "My Three Masters" - Wes Jones Intro of PKC starting at 4:52

Architectural Association London 2008: Paffard Keatinge-Clay - Odyssey of a Twentieth-century Architect

California College of the Arts, with an intro by Eric Keune, 2007

Publications

Eric Keune. Paffard Keatinge-Clay: Modern Architect(ure)/Modern Master(s). Southern California Institute of Architecture Press, 2006

Safdie, Moshe. Beyond Habitat: San Francisco: The Space Maker, 1970.

Chapter 21, pages 27-37. For context on the SFSU Design Competition.

Additonal Photo Credits: Sandy Strauss Stern, Cord Struckmann